When I analyse tap tones, I work in the unit for frequency – the Hertz (Hz). Frequency tells you how many times something vibrates in one second. With sound, that means the number of times in a second the particles of air near your ear push against your eardrum. The higher the frequency, the higher the pitch of the sound.

Musicians, naturally enough, don’t care nearly as much about this as guitar makers do. They know that if you go up an octave you’re hearing a frequency double that of where you started, and they know that the notes of the Western musical scale are at particular frequencies defined by a mathematical series known as 12 tone equal temperament.

Even if you aren’t a musician, you know that as well because you’ve listened to lots of music during your life. That’s what your ear has come to expect, especially if you’re from a Western culture.

Interestingly enough, guitars and other fretted stringed instruments aren’t very good at producing exactly the right frequencies to make a major scale sound perfect. If you have an electronic tuner, you can see this if you tune a string to its correct fundamental (eg the A to 440Hz) and then work your way up the fretboard fret by fret. Notice how cranky your tuner gets?

The frets aren’t right! That is one way to see it, but the explanation is actually to do with the physics of how real strings vibrate.

The reasons are something for another time, but musicians with really good ears – especially those who play fretless instruments like violins – are often driven crazy by what’s called the inharmonicity of a guitar. Fretless players can use subtle fingering adjustments to make their notes true.

The rest of us take it as it comes and put it down to being part of the sound of the guitar. Guitar makers pull their hats down over their eyes and quietly leave the room before they’re noticed.

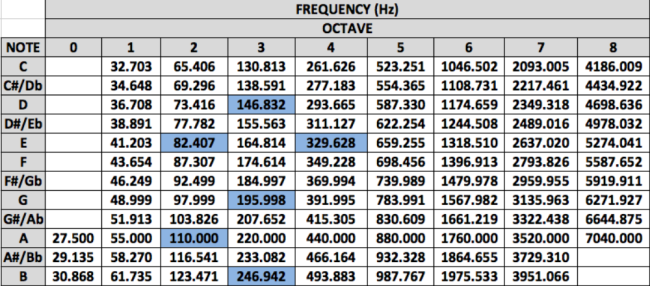

So anyway, here’s a chart showing the notes in the diatonic major scale.

The chart begins at 27.5Hz because the human ear doesn’t really hear anything much below that as a continuous sound (20Hz is considered the cutoff) . It ends rather arbitrarily at 7040Hz because most instruments don’t produce much sound at those high frequencies (but mainly because guitar makers don’t care about anything much over 5000Hz).

The standard tuning of guitar strings is shaded blue for your viewing convenience.

The octave number helps identify which note you mean: the B string on a guitar is tuned to B3 at 246.9Hz. Notice the doubling of frequency from one note to its octave above.

The little gradations on your guitar tuners that show how far above or below the string is are cents. The interval between any two notes is divided up into 100 parts, but as you can probably guess that isn’t simple because the frequency interval between two notes gets ever larger the higher you go.